Last updated: 4 Dec 2020 | 6160 Views |

Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝)

For any Chinese culture enthusiast out there, or if you’ve been learning Chinese for quite a while, it’s very possible that you have come across the “Four Great Treasures of the Study” at some point (your laoshi would certainly mention them!).

But if you haven’t, this post is a good start! Let’s get familiar with them and their significance regarding Chinese penmanship culture.

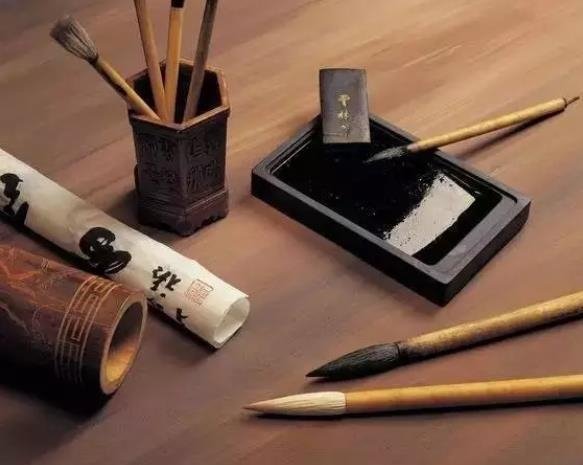

(photo credit: www.sxkzxt.com/wap/showcase.asp?id=217)

As most people know, the Chinese have calligraphic tradition which involves a lot of – you’ve guessed correctly – brushes and ink.

Dated back to as far as the North and South Dynasties (420–589 AD), the expression “Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝wén fáng sì bǎo)” basically refers to the 4 essential tools that ancient Chinese calligraphers and painters used for their trade: brush, ink, ink stone, and paper.

(photo credit: www.sxkzxt.com/wap/showcase.asp?id=217)

First and foremost are the brushes (笔bǐ) which are quite different from Western painting brushes. Chinese brushes are believed to be invented as early as 3000 years ago.

In their initial forms, they were made by attaching animal hair to a bamboo stick. The handles would later get fancier with more elaborate materials like precious wood, jade, or even ivory.

For us at YOA, this is even more straining than yoga!

(photo credit: education.asianart.org)

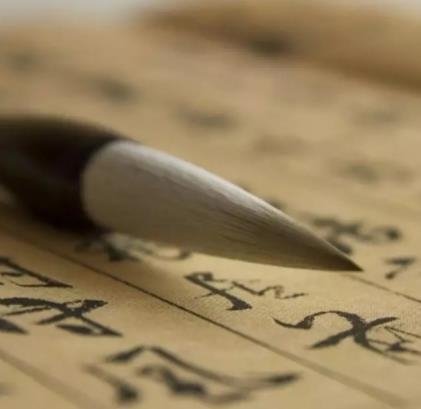

Different animal hair give distinctive stroke textures, so calligraphers and painters would stock brushes of various kinds and sizes to suit their purposes.

Most people start their Chinese calligraphy lesson with how to correctly hold a brush, which we can guarantee is way harder than it sounds!

Huimo (徽墨literally “Hui ink”) from Anhui Province, famed for its musky and aromatic Chinese medicine fragrances as well as its 1,000 years of history

(photo credit: hszywh.com)

Next is ink (墨 mò); earliest Chinese ink was believed to be made from natural minerals, and later other kinds of charred woods.

In a later period, ink would often be produced in a form of solidified ink stick made of soot and binding material such as oil, which needs to be ground into powder over ink stone before mixing with water.

Some high quality ink may also include powdered spices as ingredients.

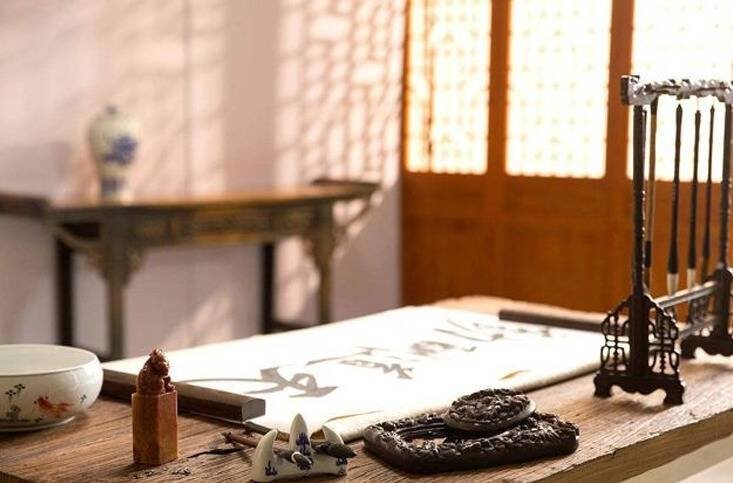

Expensive ink stones are often carved and decorated elaborately,

and considered to be highly prized possessions.

(photo credit: www.sxkzxt.com/wap/showcase.asp?id=217)

Meanwhile, ink stones (砚yàn) are basically stone/ceramic/clay slabs for grinding ink stick and containing the liquid ink once the powder is mixed with water.

The ink stick would be ground at an area before sprinkled with water on another part that acts as a basin, at the right amount and fineness that would suit the calligrapher’s purpose.

Water plays a role here in intensifying or diluting the ink’s shades.

Xuan paper (宣纸) or rice paper has been made in China over 1,000 years.

(photo credit: www.cdhbxt.com/kb/content/?109.html)

Last but not least is paper (纸zhǐ), which in a way might be the most significant out of the four, as paper is considered one of China’s four great inventions. Of course when it comes to ancient paper, the Egyptian papyrus often comes to our mind first.

But here’s the glitch: papyrus hardly resembled modern day’s paper with its thick and coarse quality. Meanwhile, the finer version of paper invented by Cai Lun during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) was closer to the paper we use today, in other words it’s suitable for the use of ink.

As a perfect medium for complex writings, its production helped promote knowledge circulation and contributed to China’s rise as one of the most advanced civilizations of ancient time. We only have to watch a few Chinese period dramas to know how complicated their ancient imperial examinations were and how all that got so tied up with studying and these four tools!

(photo credit: www.inkston.com/stories/guides/chinas-four-treasures-of-the-study)

Another fascinating thing is how each item became “treasured” by Chinese scholars over time, to the point where elaborate customs evolved out of handling and applying them, as well as how each item is attached to a particular area or region’s name that specializes in their production, like in Huimo ink’s case.

Today, Chinese parents would sometimes gift their kids with the four treasures for their calligraphy class, or as a symbolic present and blessing for the child’s education.

In our era of smartphones and computers in which kids hardly practice writing with pencils anymore, talking about these items may feel a bit anachronistic.

But if you ever get tired of the screens, basic calligraphy may just be a perfect break from the buzzing social media.

Calligraphy can be pretty cathartic (as long as you can keep your head cool over handling the brush correctly), and what you get from reading here might just come in handy!